Conceptual Questions

Return to Ode to My Father Film Guide

This section introduces conceptual questions that instructors can familiarize themselves with before they teach the film. They can be adapted for class discussion after the screening. I suggest pairing general questions with specific moments in the film that allow students to discuss the question. The four categories below are all related to one another, and questions listed in various sections can be combined to promote even more robust discussion. Questions are rendered in bold.

Ordinary Men and Everyday History

Fig. 18: (left) Duk-soo walks past a memorial in Gukje Market with his granddaughter, who was just asked him what “memory” is. Screenshot from film.

Fig. 19: (bottom) The film cuts to statues of two young girls carrying heavy objects as he replies that memory is just like the statue. It’s about, “Thinking about the old days. Things you can’t forget.” Screenshot from the film.

Ode to My Father uses the story of an ostensibly ordinary individual to explore the history of South Korea, an approach roughly modelled on Forrest Gump. Like Forrest, whose intellectual disability set him apart from his peers, Duk-soo is a marginalized character, a North Korean refugee whose background marked him as different and potentially dangerous in postwar South Korea. Despite efforts to get an education, Duk-soo’s dreams of becoming a ship captain are repeatedly thwarted by the economic demands faced by his family. He works abroad to secure financial security for his family and eventually settles down as a shopkeeper. Forrest Gump’s historical trajectory is more obviously dramatic. While Forrest becomes a remarkably wealthy man, Duk-soo ends up living a relatively modest middle-class life. Forrest repeatedly finds himself brushing past dramatic historical moments, appearing in scenes that shaped the shaped America’s social and political consciousness in the 20th century. Duk-soo occasionally bumps into famous people, but his life plays out largely on the sidelines of historical memory (except for his appearance on Finding Dispersed Families, which will be covered below). Ode to My Family is framed by significant historical events, like the Korean War, but it actually avoids entangling its characters in well-known political events that have been enshrined in popular memory in iconic photographs. The film shifts attention to a grueling economic history which is deeply intertwined with the country’s politics, but that plays out in the everyday life of the film’s protagonists in seemingly more mundane ways.

- What are the political stakes of this film? What type of historical experience does Ode to My Father offer its viewers? How is it different from other historical films students may have seen? Consider, for example, how A Taxi Driver uses the “ordinary man in extraordinary circumstances” narrative trope to explore South Korean history. How do “ordinary” people experience/participate in “history”? What “counts” as a significant historical moment?

- Early in the film, Duk-soo walks in the market with his young granddaughter, who asks him, “What is memory?” just as they pass statues of young girls carrying heavy objects (likely food and water). They appear to represent the refugees who lived in Gukje Market in the difficult postwar period. Duk-soo explains the idea of memory by pointing to the statues and explaining that memory is just like this memorial (figs. 18 & 19). How does this moment prime viewers to understand historical memory? These are anonymous statutes, not significant historical figures, but two girls who have to work hard to help their families. Consider what role gender plays here: what does it mean for memory to be defined through women’s work? Duk-soo is particularly sensitive to images of young women from this time because of his lost younger sister, but the scene does lay down questions about how men and women’s work is incorporated into historical memory.

- How is economic progress in the film visualized? How does the family home, the shop, and the market, change in the film? Where do we see the impact of Duk-soo’s sacrifices and hard work? How does the film’s opening scene, in which Duk-soo overlooks a bustling port city, present a vision of South Korea’s past, present, and future?

International Labor Markets

Labor is a very significant issue in South Korean history. South Korea’s “miraculous” economic development depended on the extreme exploitation of industrial workers. Their labor built up powerful international companies that now represent the economic might of South Korea. South Korea is now a highly developed country, one of the world’s richest nations, and home to a large middle class, but despite this great success, economic tensions are high. Many of the most well-known South Korean films, like the Oscar-winning Parasite (dir. Bong Joon-ho, 2019), are violent allegories that lay bare the income inequality that characterizes contemporary South Korea. An astonishingly high number of South Korean television series, or K-dramas, are set in workplaces where harried employees spend nights and weekends striving to deliver goods and services on time. On television, the intensity of modern work is can be an engaging driver of narrative tension, but in reality, South Korean workers are overwhelmed by work and crushed by their bleak economic prospects. Extreme dedication to the job is expected of all workers, but South Koreans no longer expect that their work will guarantee a comfortable, or even livable, life. The term “Hell Chosŏn” came into popular use around the same time that Ode to My Father was released to describe this bleak social atmosphere. Chosŏn refers to Korea’s last dynasty, which ruled the peninsula from 1392-1905, and is in this case shorthand for “South Korea.” To live and work in this seemingly prosperous nation, it turns out, is a hellish prospect.

Throughout this film guide, I have been arguing that Ode to My Father avoids dealing with South Korea’s contentious political history explicitly. Despite its outsized focus on physical labor, the film even manages to avoid confronting the history of labor exploitation and protest that roiled domestic politics. It is important to acknowledge that this backdrop of protest is missing from the film. Rather than foreclosing analytical possibilities, however, it is equally important to consider how labor is represented and how the film’s various vignettes add up to a history of the South Korean labor market. Most strikingly, Ode chooses to tell the story of South Korean development not by looking at labor history in the domestic space, but by turning out towards the world, a marketplace where South Korean labor was a popular Cold War commodity.

- Ode’s original title, “Gukje Sijang,” literally means “International Market.” The film begins with a shot of the marketplace itself, but soon moves to a rooftop in Busan where an elderly couple, Duk-soo and his wife, look out onto the city’ port and skyline. This introduction, somewhat obscured in English translation, introduces viewers to the film’s global scope. The scene also sets up a major conflict. Duk-soo asks his wife, “You know what my dream was as a boy?” She doesn’t know, so he explains, “To be a captain, steering a big ship like that.” Duk-soo dreams of having participated in the development of South Korea’s shipping industry. The irony is that he did, by working supply logistics during the Vietnam War. In fact, Duk-soo career as a migrant worker might be construed as a cynical shadow of his dream: rather than being in charge distributing South Korean goods around the world, he himself became a commodity that was shipped wherever it was most needed. How does the film present this type of mobility? How does Duk-soo’s dream contrast with the reality of navigating the international South Korean labor market? What does international mobility offer to the film’s characters?

Fig. 20: A view of Busan from the rooftop of Duk-soo’s apartment in 2014. The film’s title, Gukje Sijang, i.e., “International Market,” appears in the top right of the shot. Screenshot from film.

- Duk-soo has at least two direct interactions with the South Korean shipping industry. As a young boy shining shoes in Busan, Duk-soo meets the founder of Hyundai, a construction firm that went on to become a giant conglomerate best known to consumers as a car manufacturer. At the time of their meeting, the businessman’s goal of building ships seems outlandish, but Hyundai is today the world’s largest shipbuilder. In Vietnam, Duk-soo is shown wearing a uniform of the fictional company Daehan. The name stands in for a number of South Korean firms that operated in Vietnam during the war, including Hyundai. It also translates to “the Great Han,” and coincides with the first two terms in the official name of South Korea: Daehan Minguk, or the “Great Han Republic.” What does it mean that Duk-soo works for a company that is literally called “South Korea” while supplying American forces in Vietnam? How does the film represent South Korean corporations and their relationship to ordinary South Koreans, here and in the earlier sequence with Hyundai?

- In West Germany, Duk-soo works as a miner. Before he travels to Europe, he has to undergo a set of tests. First, he demonstrates his physical prowess. Since he has been loading goods at the port, he is stronger than the other men who have applied for the job. The South Koreans at the recruitment office are small, and the film implies, weak. Miners who worked in West Germany reported that their relatively small size was an asset, since it allowed them to work in smaller spaces and remote parts of the mine that larger European men could not fit. This, of course, also made their jobs more dangerous and difficult. When Duk-soo faces his second test, an interview, he almost fails when it becomes apparent that he has no mining experience, but in a moment of begins singing patriotically. Flustered, the company officials administering the test certify him as a good candidate because of his strong patriotism. In reality, most men who went to work in West German mines had no experience, so like the small stature of most workers, this would not have been a deal breaker. Nevertheless, the film lingers on these moments. Why? What is communicated in these sequences? What makes a good worker? How are laboring bodies (and psyches) pictured here and in later scenes in the film?

- Ode to My Father is largely focused through the experience of Duk-soo, and through him, male labor. But in West Germany, the film lingers on the life and work of South Korean nurses. Like their compatriots, the nurses worked hard in West Germany. How does the film present the work of the nurses? Notice that unlike the men, they are skilled professionals who are learning new skills as they work in West Germany, but their situation is not necessarily significantly better. Compare and contrast the conditions each group works and lives in and how they overcome the relatively isolated conditions in which they find themselves living.

Fig. 20: (left) Youngja, dressed in an impeccably clean uniform, intervenes with West German mine bosses on behalf of the South Korean miners. Screenshot from film.

Fig. 21: (below) The “poor, luckless Koreans who came to this distant land just to earn money.” She initially speaks German, but as the boss refuses to help, begins wailing in Korean, and moves the men to disregard orders and rescue their comrades. Screenshot from film.

Cold War Repetition

The Vietnam War was, in many ways, a repeat of the Korean conflict, albeit one that ended worse for the United States. While the Korean War built up the postwar Japanese economy, Vietnam allowed South Korea to finally jump start an economy that had been stagnating since the 1950s. In the film, Duk-soo experience in both West Germany and Vietnam is explicitly marked as the repetition of war trauma. It’s possible to explain his reactions in both cases as a psychological effect that is personal to this character, but the danger inherent in both forms of labor, mining and military supply logistics, suggests that there is larger repetitive structure at work.

Repetitions:

- While the men are working in the mine, gas pipes begin to overheat, and eventually, they explode, Duk-soo and Dal-gu are trapped in a collapsed tunnel. In Youngja’s hospital, nurses tend to miners who like war casualties. At the mine, the West German supervisors decide it’s too dangerous to evacuate those trapped inside, even when Youngja tries to intervene on their behalf. The South Korean miners, however, are mobilized by her speech and rescue their comrades.

- In Vietnam, Duk-soo is charmed when he gives chocolate to a young Vietnamese boy, recalling his memories of receiving chocolate from American soldiers during the Korean War. In a moment of solidarity, the boy intimates to Duk-soo that something is about to happen, and Duk-soo manages to move in time to survive a suicide bomb attack.

- In the final scene in Vietnam, Duk-soo and Dal-gu happen are stuck behind enemy lines when Saigon falls. They happen upon a group of Viet Cong fighters, but they are rescued by Korean marines. The group goes to a village where the Daehan workers had built a pier, a structure that the marines destroy as they retreat to fall it from falling into enemy hands. Just as they are ready to depart, villagers ask to be evacuated. As they load people onto their military boat, the Viet Cong attacks, but ultimately, the evacuation is successful.

Fig. 22: (left) Residents of Hungnam watch as their city explodes from a boat that is evacuating them to South Korea in December, 1950. Screenshot from film.

Fig. 23: (below) South Korean workers, marines, and Vietnamese villagers react to the force of the explosion behind them as they flee their village in 1975. Screenshot from film.

- How do these three scenes repeat earlier sequences in the film? There are clear thematic and visual references to the Hungnam Evacuation and Duk-soo’s experience as a child in Busan. How is this repetition visually reinforced?

- What changes in each case? In the Hungnam scene, a South Korean implores an American commander to save the refugees. In Busan, Duk-soo sees American soldiers giving children chocolate. In the subsequent scenes, the roles of the savior/giver change. How does the dynamic between South Korea and other nations shift? What communities of solidarity are produced in each scene?

- What function does the flashback have in these scenes? How does underscoring the continuity between the original trauma (Korean War) and the ongoing violence in Duk-soo’s life impact the meaning of the film? Why is it important for these three moments to be connected, for Duk-soo’s story, but also for the larger narrative of South Korean labor that the film is presenting?

- The first Vietnam sequence, in which Duk-soo gives candy to a Vietnamese boy, combines nostalgia and terror. What effect does this uncanny combination have? Duk-soo appears nostalgic as he remembers his own boyhood. To get chocolate, however, Korean children put on grotesque dances for laughing American soldiers in Busan, not quite a “cute” memory. The boy recognizes Duk-soo as a South Korean and alerts him to an imminent sabotage of the military police office behind them. This moment of Asian solidarity is highly ambivalent given South Korea’s state-mandated anti-communism and alignment with US interests. Why such ambivalence?

Mediated Rituals of the Nation

Ode to My Father includes several sequences in which groups of people convene around media devices to listen to or watch together. Though the circumstances differ, in each case, the crowds that engage with media technologies are presented as a South Korean nation that listens, watches, and even cries together. In his famous study, Imagined Communities, the historian Benedict Anderson argues that modern nation states are produced through the ritualized consumption of mass media. Reading a newspaper, for example, produced a sense of belonging to a national polity because everyone is reading it in the same national language, on the same day (usually in the morning), and with the awareness that others are reading the same material.

Fig. 24: (left) People gather around to listen to a radio announcement declaring the Korean Armistice Agreement that emanates from a store on a narrow street.

Fig. 25: (below) Duk-soo’s mother is in the crowd and asks another woman if she can go home.

Fig. 26: (right) The film cuts to another crowd, elsewhere in the city, where Duk-soo, having just asked the same question, is told he cannot go home.

Fig. 27: (bottom right) The scene ends with an extreme long shot of the street where the second group is listening, a broader avenue. All screenshots from film.

Our contemporary media landscape is much more fractured, so it’s hard to imagine that a everyone will read the same news articles or watch the same broadcast, but throughout the 20th century, media technologies like radio, television, and cinema both addressed and created a (homogenous) national audience. It is not just that a broadcast was produced for the nation, it also produced the nation by binding the audience into a community that experienced its content together. Each historical vignette in the film includes a scene in which South Koreans are hailed by media, meaning that they pulled into a ritual that galvanizes them as South Korean.

- 50s: The Korean Armistice Agreement was signed on July 17, 1953. In the film, people gather to listen to a radio announcement by the South Korean president, Syngman Rhee, concerning the agreement in multiple locations in Busan (figs. 22-25). At one shop, Duk-soo’s mother asks others in the crowd if she can return to the North. At another, Duk-soo inquires about the same thing and finds out that he cannot return.

How is the armistice presented in this scene? What national body does the announcement address? Notice that in both cases, Duk-soo and his mother are the only vocal North Koreans in the crowd, signaling that they don’t quite belong.

Fig. 28: (left) A cinema in 1963 plays Daughters of Pharmacist Kim, a melodrama.

Fig. 29: (below) In a reverse shot, the film shows the audience. The small light above them in the center of the shot is the projector.

- 60s: Ode to My Father features a metacinematic moment in its 1960s section. In the scene, the initial shot shows a theatrical screen playing The Kim Pharmacy’s Daughters, a 1963 melodrama directed by Yoo Hyeon-Mok. The scene on screen is close to the end of the emotionally devastating film. In a reverse shot, Ode shows the film’s audience. A group of schoolgirls weep in the front row, moved by the family’s tragic fate. As the multi-generational saga that spans Korea’s recent history plays on screen, Dal-gu and Duk-soo discuss their plans to go to West Germany in the projection room. South Korean cinema experienced a “golden age.” Many classic films from the period, including Daughters, explored the nation’s history through melodrama, a genre that showcases righteous suffering. While the audience in Ode is crying in response of the bleak events on screen, ostensibly identifying with the characters’ plight, the two main characters plan an escape, however temporary, from hardships in South Korea.

- How does this scene characterize the role of cinema in the South Korean 1960s? What does cinema offer to the people who watch it? Dal-gu, dressed like James Dean in a poster behind him (fig. 5), for example, has also been moved by film. His engagement with foreign cinema, however, has pushed him to leave his country, not cry for it.

Fig. 30: Duk-soo and Youngja stand and recite the “Pledge of Allegiance to the Flag” as flag is lowered at a nearby building. Screenshot from the film.

- 70s: The 1970s media experience in Ode is more sinister. Duk-soo and Youngja have been arguing in a public park about the former’s decision to work in Vietnam during the war. Youngja is opposed, pointing out that Duk-soo has always been sacrificing himself. “It’s time for you to live for yourself, not for others,” she says. During their argument, the “Pledge of Allegiance to the Flag of South Korea” begins playing over loudspeakers. A male voice accompanied by martial music intones the text. The subtitles read, “I, standing before our noble flag, do solemnly pledge allegiance to the Republic of Korea, and its glory, liberty, and justice.” This is the text of the revised pledge that was introduced in 2007. The film uses the original, introduced nationwide by Park Chung Hee in 1972. That pledge promised to “offer my body and mind to the never-ending glory of the fatherland and nation.” There was no mention of liberty or justice. In the early 1970s, South Koreans became (again) dissatisfied with their authoritarian government. To curb opposition, Park declared a new republic and promulgated the Yushin Constitution in 1972, effectively staging a coup against himself. Under the Yushin Constitution, the government became more draconian and expected utter loyalty of all citizens. This is why everyone stands to recite the pledge. The man who looks at Youngja, so bereft that she remains sitting, has an ambivalent expression. It’s equally valid to say that he is suspicious of her as that he is afraid for her, should her lack of patriotism be reported to authorities.

- What is the significance of this nationalist display? How does its compulsory nature change the meaning of a display of loyalty? How does the demand to offer one’s “body and mind” for the country correlate with the conversation that the couple was just having? What, does the film imply, Duk-soo been sacrificing himself for, a private or national goal? How does this scene tie the personal and the political together?

Fig. 31: (left) A group of people watch Finding Dispersed Families next to a bus station.

Fig. 32: (below) The next shot reveals the television screen that they are looking at.

Fig. 33: (right) The film then cuts to another location, another public television, this time in a market, showing the same program. Screenshots from film.

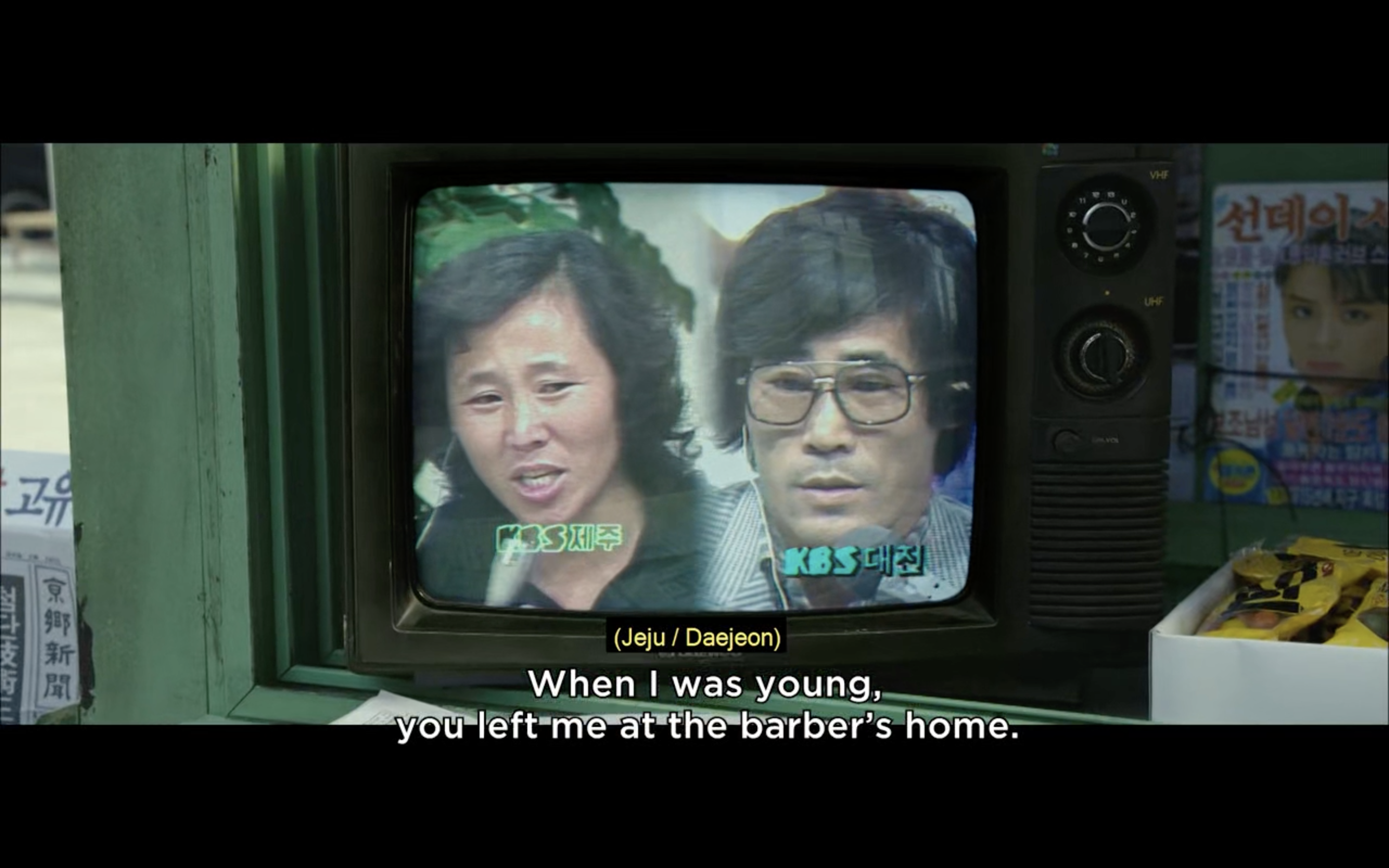

- 80s: The TV event in the last historical vignette is the film’s most prominent engagement with mass media. The 1983 broadcast of Finding Dispersed Families is first introduced through the television set itself. In the first 1980s scene of Ode, Duk-soo sits at his store while the TV begins broadcasting the show. This initial moment is followed by a montage of shots that reveals that Duk-soo has travelled to Seoul in an effort to find his lost family. For about a minute of screen time, Ode shows how the South Korean public experienced Dispersed Families, both on Yeouido Plaza and on television. The film cuts between shots of groups of South Koreans watching televisions together in various locales. Initially, a group watches at a stall near the main train station in Seoul, then near a bust station (figs. 31-33), then an unnamed market, then, finally, back at Duk-soo’s store in Busan, where Youngja and neighbors watch what is happening on screen.

- What does television do in this sequence? Notice that in all cases, people are watching televisions communally on the streets. This is not an issue of scarcity. By the 1980s, televisions were widely available in South Korea, so many people watched this program at home. Ode shows only one family watching at home, Duk-soo’s relatives gather at home to watch him on the program a little later in the film. Here, television is not private, but rather a public ritual that brought together strangers who cried together while watching.

- How is this scene different from the previous moments described in this section? In some ways, it echoes the radio address, since it’s a broadcast that the whole nation watches, but it also resonates with the cinema scene, since the audience is crying. Finally, unlike the “Pledge of Allegiance” sequence, the Dispersed Families broadcast is not engineered as a political display by the government. It is, however, a highly staged event. How does the film portray the interplay between people and television producers? Why does the broadcast retain a feeling of authenticity, even given the tremendous efforts of the production team that are shown on screen?

This film guide was developed by Julia Keblinska, The Ohio State University and is available online for classroom use worldwide. The film guides can be accessed at EASC's Film Guide page.